A warm Sunday morning in May. I’m up (too) early and heading off to my local football ground. Its cup-final day for the local youth leagues and I shall be officiating in a couple of games, first as an assistant referee, then I shall swap with the man in the middle who will be my “Lino” as I referee the game.

I arrive early, park up and, as I step out of my car, another vehicle pulls up and a young man, also clad in black, hops out – my fellow referee. There is a glimmer of recognition as we shake hands and I begin to quiz him about his background so I can work out where I have encountered him before. It turns out he’s on the books of a local League 2 side and I’ve ref-ed some of their U16 trials games and will have seen him on the pitch there.

We chat some more as we wait for kick off. He’s currently in Year 11 at a local school, is quietly confident about his forthcoming GCSEs and is even more excited to tell me that he has been signed on as a “Sixth Form Scholar” at the aforementioned League 2 club. No mean achievement, and he is right to be proud.

I quiz him further (I’m a nosey old git!) He’ll be going to the sixth form college in the town of his club – he admits he probably wouldn’t have chosen that college if it weren’t for his football commitments, but it is a condition of signing on as a “scholar.”

He also tells me that none of the current “lower sixth scholars” at the club have been signed on for the “upper sixth.” They have all been “let go” – they will, of course, continue their studies at the local college but ties with the football club have been severed.

Another school, another Year 11, another Football Club (but also in League Two.) I found myself chatting to this student, asking what he would be doing next year. Again, it was with some pride that he told me he would be joining …… FC as one of their football scholars.

We chatted away, I was interested to see what this meant in practice. Like the young ref mentioned above, this lad will spend several days each week training with the club, and several days each week at the local college. Asking him what he would study he told me that all football scholars at the club followed the same academic course.

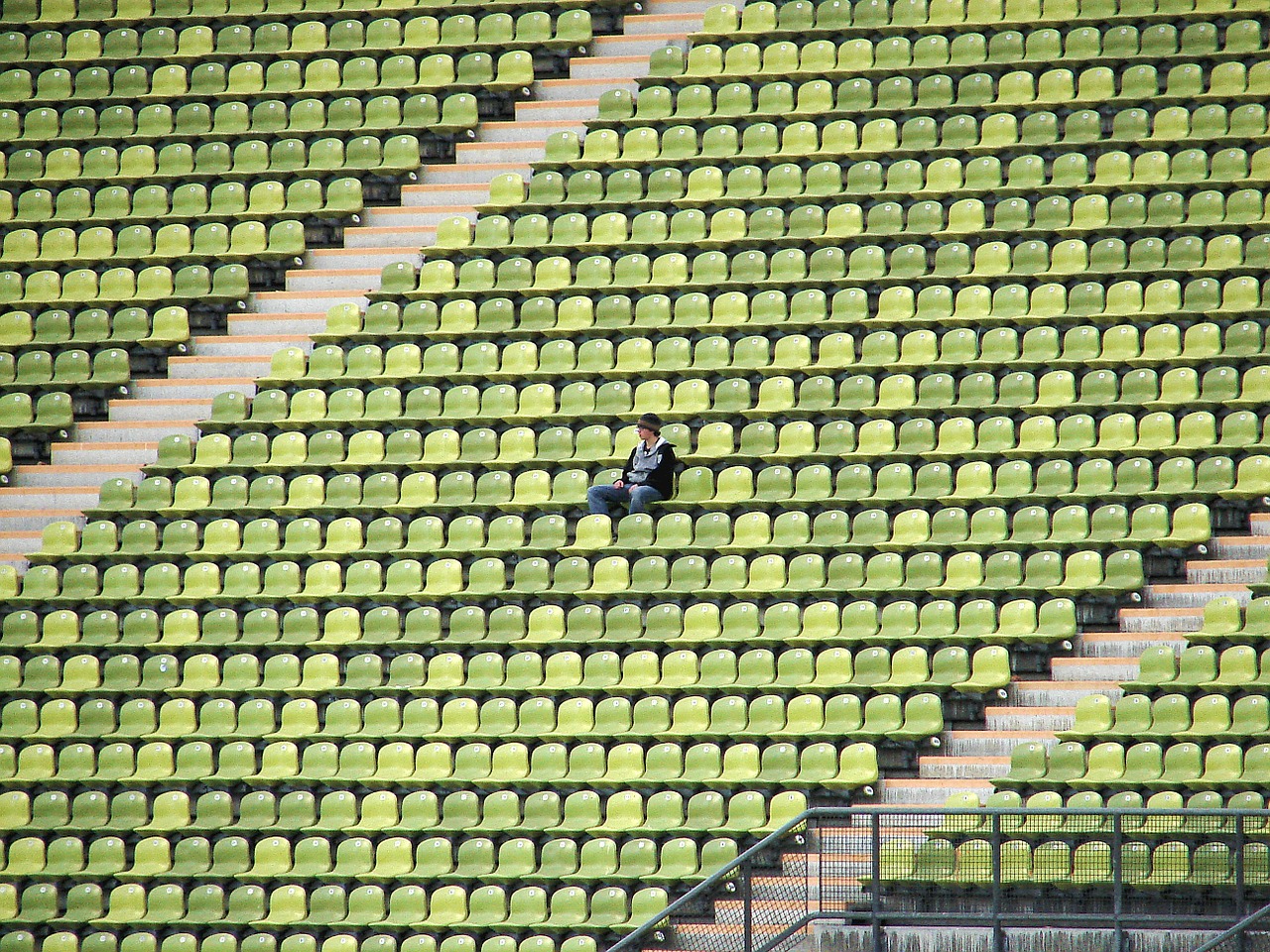

And that set a few alarm bells ringing. These boys are mortgaging their future on the possibility, and, as we will look at below, a slim possibility, of “making it” as a professional footballer. The football scholars will have different skills and strengths on the pitch, and it will be the same in the classroom. To shoe-horn them all onto the same academic course, to deny them the choice of studying the subjects that they want to study is doing them a disservice. But with the lure of of a glimmer of a pro-contract in two years time, heads are easily turned.

If they make it, does it really matter that they’ve missed out on A Level Maths, or English or Geography or whatever? No, it doesn’t. But most won’t make the grade.

The Independent recently published an article promoting a book: “No Hunger in Paradise: The Players. The Journey. The Dream” by Michael Calvin, who documents the sometimes seedy story from schoolboy to professional footballer, a story littered with shattered dreams, shady agents and broken promises. In it, he offers the staggering stat that only 180 out of the 1.5 million boys who play organised youth football in England will go on to play in the Premier League. That’s a success rate of 0.012%

I thought I’d do some of my own sums, and they back up the authors claims. I’ve made many generalisations, but I think I’m in the right ball park. Here are my calculations.

20 Teams in the Premier League each with, say, a playing staff of 30, so that’s 600 players playing in the Premier League.

Assume a career length of 15 years, so each year one fifteenth of the players will retire. To replace these we need 1/15 x 600 new players each season, or 40 new footballers each season, 40 youngsters to take the place of those who have reached the end of their playing days.

There are 48 counties in England, so its not enough to simply be the best player in your county, you’ve got to be better than that. And that’s before we even factor in overseas players.

Another ballpark figure, let us say that half the players in the Premier League are English, half not. So we probably only need 20 new English lads each year to join the elite ranks of Premier League footballers. To succeed, statistically, you’ve got to be – at least – the best player in your county and the neighbouring county.

But of course, you don’t have to play in the Premier League to enjoy a successful, and financially rewarding, career in football. Those plying their trade in the Championship, League One and League Two will enjoy a good living and lifestyle. And as you drift further down the football pyramid their is still scope to make a significant additional income from playing the game. (Alas, my playing days were so far down in the roots of “grass roots” football, I was paying to play, a long way off being paid to play!)

I don’t want to deny anyone their dreams and I wish those two young men I mentioned above the very best of luck – it would cheer me enormously to cheer them on a professional football pitch – but I can’t help but worry that, because of choices that are being made for them by their clubs, doors are being closed to them, when education should be about opening as many doors as possible.

2 Trackbacks

[…] Source: One in Eight (thousand) […]

[…] just read this, and it made me think about something which has bothered me for quite some […]