“We live in unprecedented times” is, perhaps, a somewhat overused phrase of the last six months, but yesterday it was apt as the unprecedented happened.

In their match against Manchester United, Brighton and Hove Albion hit the woodwork* 5 times in the game. This (one team hitting the woodwork 5 times) has never happened before in a Premier League fixture.

(* “hitting the woodwork” in football is when you shoot, and the ball rebounds off either the posts or the cross bar. For the neutral spectator it is an exciting and dramatic moment as the ball cannons back – with an audible thud – onto the field of play. For the attacking side it is, of course disappointing as they hope, instead, to see the net bulge, whilst the the defending team breath a collective sigh of relief as a goal is thwarted.)

So how likely is this? Hitting the woodwork five times in a ninety minute game? Should we be surprised that it happened, or perhaps surprised that it hasn’t happened before?

On of my regularly readers, Steve from Cheltenham, got in touch with me to walk me through some maths he had done to calculate the probability of this happening:

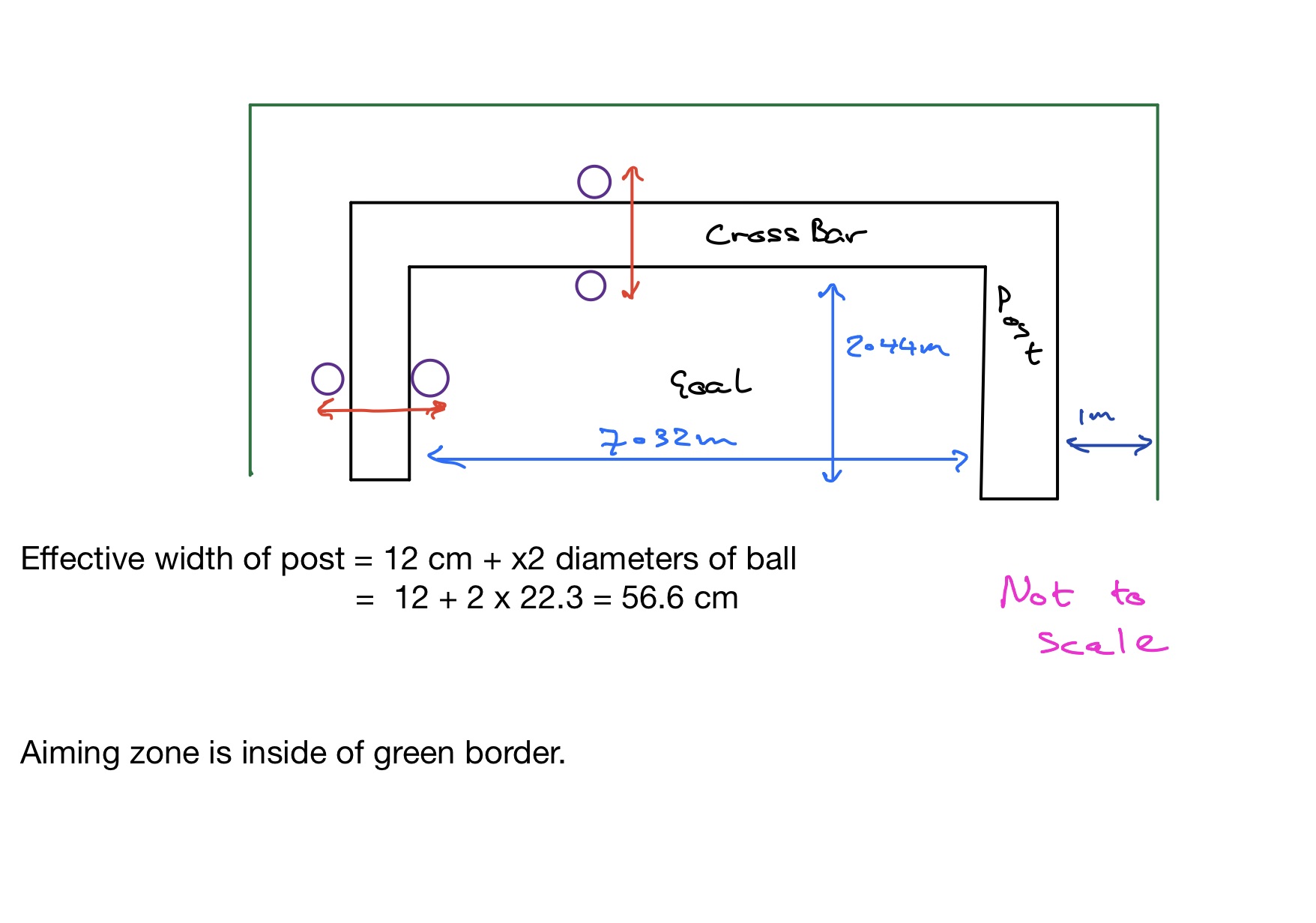

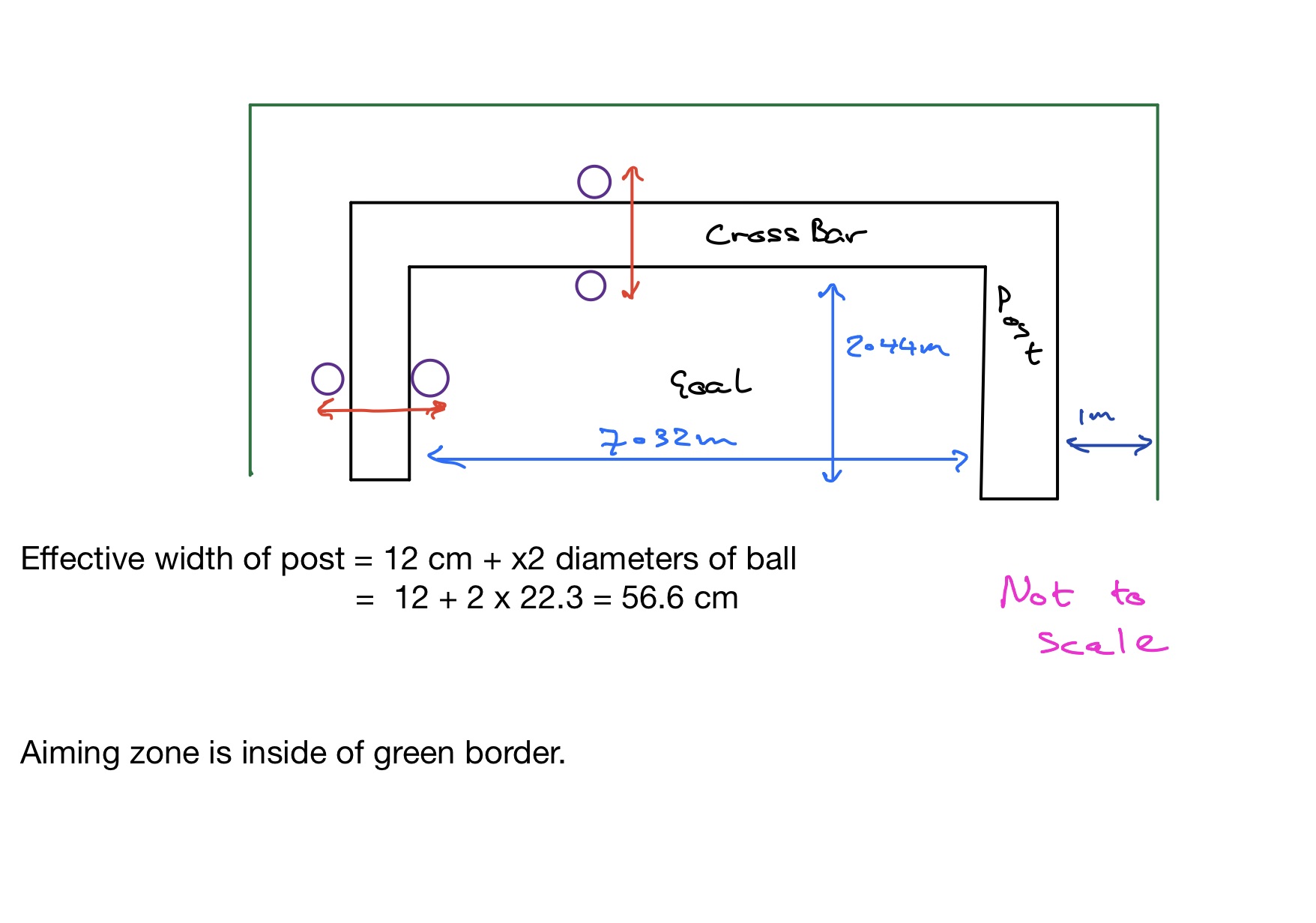

Assume that every shot is always within a rectangle that extends to 1 metre around the outside of the goal (of course, this isn’t always the case, but we need to make some assumptions if we are to create a working model.)

Assume that there is no aiming and hence every point within that rectangle is equally likely to be hit (another assumption to simplify our model)

The total area of the aiming zone is 34.03 m2

The area of the posts and bars are not what you might first think …

In our initial work, we just found the area of the posts and bars, but this would assume we were modelling the ball as a point. But actually, the centre of the ball can miss the post, but the ball still strike it, so the effective width of each post is the 12cm of the post, plus x 2 diameters of the ball (the diameter of the ball is 22cm) Hopefully the sketch picture below adds some clarity:

This make the “effective” area of the woodwork 6.83 m2

Therefore the probability of hitting the woodwork is 6.83/34.03 = 0.201 (to 3 decimal places)

Brighton had 18 shots in the match, so we can use a binomial distribution with n=18 and p = 0.201 to find the probability of hitting the woodwork in 5 out of those 18 shots. Using the standard notation:

When B ~ (18.0.201), P(X=5) = 0.152

or, the probability of hitting the woodwork 5 times in yesterdays game was about 15%, so unprecedented, yes (because it hasn’t happened before), unlikely? yes, but perhaps not too surprising and maybe we should be wondering why we haven’t seen it happen before …